We tend to blame God for natural disasters. God is responsible for natural processes such as earthquakes, but it is usually humans who turn them into disasters. As Bob White puts it, many ‘“natural disasters” … are not natural at all – in fact, we might even go so far as to call them “unnatural disasters”, because human agency has turned an otherwise good feature of the natural world into a disaster’ (p. 11).

We tend to blame God for natural disasters. God is responsible for natural processes such as earthquakes, but it is usually humans who turn them into disasters. As Bob White puts it, many ‘“natural disasters” … are not natural at all – in fact, we might even go so far as to call them “unnatural disasters”, because human agency has turned an otherwise good feature of the natural world into a disaster’ (p. 11).

Bob White is a professor of geophysics at Cambridge and Director of the Faraday Institute for Science and Religion. In recent years he has authored, co-authored or edited a good number of books looking at scientific and environmental issues from a Christian perspective, such as Hope in an Age of Despair: The Gospel and the Future of Life on Earth (click for my review).

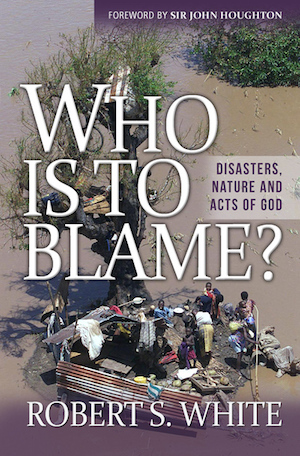

His 2014 book, Who is to Blame? Disasters, Nature and Acts of God, is clear and accessible. The first half draws on his expertise in the earth sciences in describing natural disasters, and the second half offers some perceptive biblical reflections.

The book starts by making a distinction between natural processes and natural disasters: ‘it is almost always the decisions and actions of humans which turn an otherwise beneficial natural process into a disaster’ (p. 10). The processes we think of as ‘disasters’ or even as ‘natural evils’ are, in fact, essential for life on earth. For example, volcanoes ‘continually cycle to the surface of the earth huge volumes of minerals essential for life’, and floods are ‘a means of distributing fertile soils’ (p. 27).

There follows a whole catalogue of natural disasters, in which such natural processes were turned into disasters by human actions (or inactions). We are confronted with the sober realisation that ‘Sometimes in excess of 99 per cent of casualties in any given disaster can be attributed directly to human agency’ (p. 118). This applies to earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, floods, famines, and more. For example, in the case of the earthquake in Haiti in 2010, corruption and ‘neglect by its former colonial masters’ led to a situation with ‘poorly built concrete buildings, coupled with construction on unsuitable slopes’. As a result, the death toll was over 230,000. In contrast, an earthquake of a similar size in California in 1989 ‘killed only 57 people’ (p. 50).

The cause of these natural disasters can be traced back to the fall. When humans fell into sin, this disrupted the relationships between humanity and God, and between humanity and the rest of creation (pp. 133-4). This is not to say that animals didn’t die prior to human sin, but the physical death of humans is described as a consequence of sin (p. 134). Adam and Eve are taken to have been real people, though not the progenitors of the whole human race (p. 123). They are described in Genesis as living in the Garden of Eden, which was distinct from the ‘harsh world’ outside the garden (p. 126). White doesn’t seem to be explicit on this point, but the assumption seems to be that the first humans, prior to the fall, would have enjoyed some kind of protection from the potentially lethal effects of powerful natural processes.

Three specific examples are taken from the Bible towards the end of the book.

First, there is Joseph and the famine in Egypt. The famine was sent by God, not for a specific reason (such as being a punishment for sin), but God provides advance warning through Joseph, and enables preparations to be made. As a consequence, a natural disaster is averted. (Does this point to how things would have been prior to the fall?)

Second, there is Job. One of the lessons from Job’s sufferings is that ‘we should not and cannot expect to understand all of God’s dealings this side of heaven’ (p. 171). Suffering will always remain something of a mystery to us.

Finally, there is Jesus, and his response to natural disasters in Luke 13. As in the previous chapter of Luke’s Gospel, Jesus focused people’s attention on the future, and on being prepared ‘to meet Jesus when we die’ (p. 175). But he also gave instructions about how to live in the present. If we are to ‘give to the poor’ (Luke 12:33), this will mean using our resources to help those who are at risk of natural disasters (p. 176).

This is surely what Jesus would want us to do, using our understanding of his creation for the good of others, and working to enable his creation to reflect his glory as he intended it to (p. 183).

So who is to blame? We should not be hasty in blaming God. Generally, it is well within our powers to prevent massive loss of life through powerful natural processes, and it is generally people who are to blame when there is a massive natural disaster. This is a very important point to make, and makes a big difference to how we respond to natural disasters (such as the Boxing Day tsunami of 2004).

However, I would have appreciated more discussion about how things might have been prior to the fall, and about how things might be in the new creation. How might people have been protected from suffering prior to the fall, in a world with floods, volcanoes and earthquakes? And, if such processes are essential to life on earth, then will they exist in the new creation, when God makes ‘all things new’ (p. 181)?