Science conventionally proceeds by "methodological naturalism", meaning that it does not "allow consideration of any hypothesis that implies, e.g., that life has been created by God, or that there has been any other divine intervention in history", in the words of Leonard Brand, a professor of biology and palaeontology and a Christian, taken from his very helpful 2006 article, A Biblical Perspective on the Philosophy of Science (Origins, 59, p. 14).

Contrasting his model with the standard approach to science he writes:

This model begins with the assumption that science is an open-ended search for truth, and is not willing to accept any rules that will restrict the search. Science as a game, following an arbitrary set of rules, does not interest me. One such arbitrary rule, the philosophy of naturalism rejects any hypotheses that imply supernatural intervention in the universe at any time, past or present. But the absence of unique events (supernatural or otherwise) should not be assumed, but should be a hypothesis to be tested. If we wish to consider whether there were such interventions, and to examine evidence relevant to that question, naturalism must be set aside so that the search can proceed unhindered (p. 30, see also p. 14f.).

Many Christians adopt methodological naturalism, seeing science and theology as "parallel but separate" ways of seeking knowledge. How does this work out in practice?

For them, science must generally proceed without interference, and religion seeks answers only to questions that science cannot address. Religion and science are kept separate, but actually they are only partially separated by a one-way door. In their system religion can learn from science, but science does not learn from religion, and religion does not “correct” science (p. 17).

As an alternative, Brand advocates a real two-way dialogue between science and religion:

This model encourages active interaction between science and religion in topics where they make overlapping claims, because both are accepted as sources of cognitive knowledge about the universe. Allow feedback between them, to encourage deeper thinking in both areas and provide an antidote to carelessness on both sides. Both religion and science can make factual suggestions to the other, which can be the basis for careful thought and hypothesis testing. This model respects the scientific process, but also recognizes truth in Scripture (p. 13).

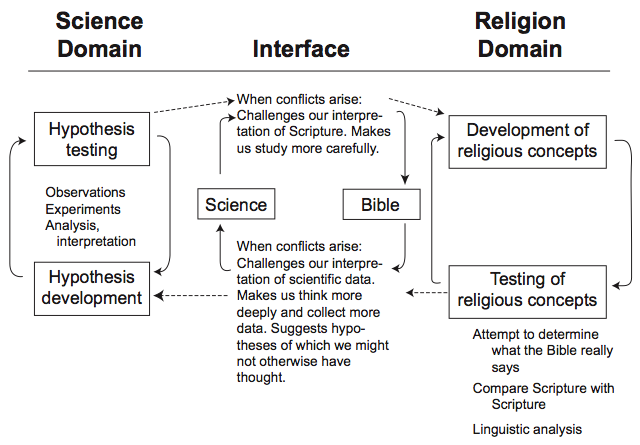

The approach developed in more detail in the article, but this diagram captures the essence (p. 33):

Working this out in practice will be far from trivial, but I'm convinced this is the kind of approach Christians should be taking as scientists.