...it seems probable that most of the grand underlying principles have been firmly established...

The words of Albert Michelson, Nobel Prize-winning physicist, in 1894.

But these words would have fit comfortably into many of the 60-70 presentations I sat through this week as part of "Outstanding Questions for the Standard Cosmological Model" at Imperial College, London.

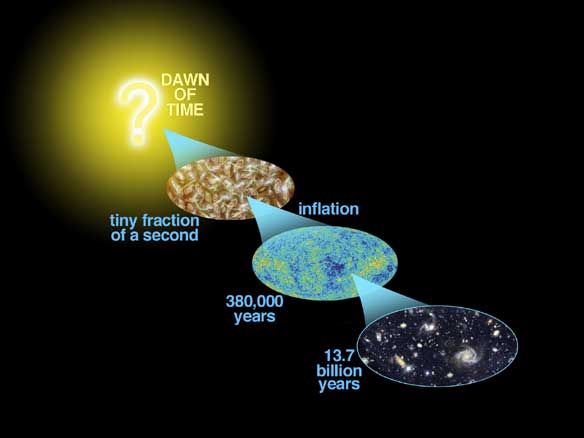

Cosmological research has within the last few decades been converging towards a certain "standard model". The Universe is now taken to be flat, expanding and accelerating, composed of ordinary matter, dark matter and dark energy, and filled with structures that grew out of small fluctuations in the early Universe.

So is this model right? That, I suppose, was the question behind this conference.

The "standard model" is not without its successes. Douglas Scott summarized a few of these in his talk: for example, years before observations were able to offer confirmation, it was predicted that both the cosmic microwave background and the spatial distribution of galaxies would display the signature of acoustic oscillations (sound waves).

But nor is it without its challenges. These are mainly related to dark matter and dark energy: can we really claim to have a firm model for the Universe when we know almost nothing about 96% of it?

So what's the verdict?

There's clearly something in it - the successful predictions of the model aren't just coincidences. But, as Albert Stebbins pointed out in his conference summary, paraphrasing Einstein, "The most problematic thing about the universe is that it is too explainable" (or words to that effect). This is because there is often more than one plausible explanation for any given set of observations. Scientific models are always tentative - our best guess until someone thinks of a better idea. So have we discovered the true model? We can't say. All we can do is look for consistency (the data are consistent with Model A) and make comparisons (the data suggest that Model B is to be preferred over Model C).

So as the jury gets to work on this task, here's my advice to them:

- The first stage is to come up with some ideas. Our models are no better than our imaginations. Reflect long and hard on the evidence. Make just a few really basic assumptions, and stare at the hard facts to see what they suggest to you. Be creative. (Science is one of the arts, you know!)

- Established models will always need refining. But resist the urge to bolt on appendages whenever you encounter difficulties. Keep going back to the foundations of the model - don't treat it as a black box that can't be taken to pieces. For example, as several of this week's speakers suggested, is it possible to re-formulate general relativity in such a way that dark energy and dark matter are no longer required?

Fortunately, the jury doesn't have to return a definitive verdict (although the individual members of the jury will feel compelled before too long to champion their personal favourite model - sitting on the fence is not comfortable - but that's another story).