What are we to do with the apparent conflict between science and the Bible when it comes to origins?

One approach is to shrug our shoulders, declare it to be a mystery, and try to get on with life. This, I confess, has essentially been my approach over recent years. Previously I would have been quite outspoken as a young-age creationist, but I’ve become much less willing to simply dismiss what seems to be a strong scientific consensus. But I’m still unconvinced that the biblical account of creation, the fall, sin and death can easily be reconciled with millions of years of evolution. I’m sure God knows the answers; does it really matter if I don’t? Can’t I just live with the uncertainty?

But I’m not sure this is good enough – at least, not for me personally. I have a PhD in astronomy, and I’m training to be a church minister. I should at least be able to shrug my shoulders in a more informed way!

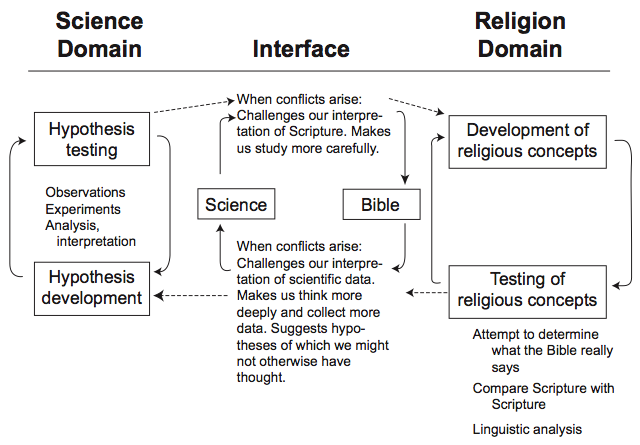

But how is one supposed to deal with the apparent conflicts? I’m convinced that Leonard Brand hits the nail on the head with this diagram (which I shared a few years ago):

When conflicts arise between faith and science, this should lead us to ask difficult questions of both faith and science. But as we do so, we recognise that each has its own integrity.

So it’s time for a bit more reading…

First off the shelf is the 2009 book, The New Creationism, by Paul Garner, a UK-based creationist researcher and lecturer. In Leonard Brand’s diagram, this book takes us into the domain of science.

First off the shelf is the 2009 book, The New Creationism, by Paul Garner, a UK-based creationist researcher and lecturer. In Leonard Brand’s diagram, this book takes us into the domain of science.

Paul Garner’s book deals with various scientific areas in turn. Refreshingly, the focus is on the merits of the creationist models, rather than on the weaknesses of the evolutionary models. (It’s very easy to pick holes in any scientific model. But it’s fairly pointless to do so, until you can come up with a better idea.)

So is it possible to construct scientific models, inspired by the Bible, which make good sense of the scientific evidence?

Well, possibly. And here we hit a difficulty. Decent scientific models take decades of hard work. And even then, there are no scientific theories that can demonstrably explain all of the evidence. The real world is much too complicated for that. At best, all we can say is that a scientific model seems plausible, all things considered. So if a creationist scientific model seems weaker than an evolutionary scientific model, that could be because the latter has a massive head start. It’s hard to tell.

But contrary to what some may say, science is not an entirely subjective exercise, in which your interpretation of the data is merely a product of your personal presuppositions. It is possible to be a little more objective than that. My faith presuppositions may well inspire me to come up with a particular scientific model, but does that model actually make sense of the data? Or does it fly in the face of all the evidence?

So what we’re looking for here is at least some hint of plausibility. Do these creationist models have even a vague ring of truth to them? If they do, then it’s probably worth spending a bit more time on the science side of Leonard Brand’s diagram. If not, then perhaps it’s time for a more critical examination of the religious concepts we have been assuming.

Let me attempt to summarise the book, with the following question in mind: Do the creationist models have at least a superficial air of plausibility to them? Does it seem as though they might conceivably be able to explain the scientific evidence, given a few million man-hours of research? Let’s see…

Part I (chapters 1-3) deals with The heavens and the Earth. This is the weakest part of the book, in terms of creationist scientific models. We are left with little more than the creationist cosmological models of Russell Humphreys and John Hartnett. Neither of these models even attempts to explain much more than how it is we can see galaxies that are billions of light-years away, if the universe is only thousands of years old. And neither model has gained much support (on the contrary). But the Big Bang cosmological model provides an excellent explanation for a vast amount of astronomical evidence, and it is difficult to imagine how this could be explained within a young-age framework. (See this paper for some examples.)

Part II (chapters 4-7) deals with Questions of time. After a chapter on the biblical material, we are introduced in chapter 5 to flood geology. The hypothesis that much of the fossil record was laid down during the biblical flood does have some merits to it. It provides an explanation for two lines of evidence. First, there is the way in which the rock layers were formed. ‘Many of the Earth’s sedimentary rock layers appear to have formed rapidly’ and ‘Many of the cross-beds in the geological record are so large that they must have been formed by high-velocity water flows more powerful than those that are observed today’ (p. 82). This is the kind of thing you might expect to find, if there had been a global flood. Second, ‘the time between the deposition of each layer appears to have been quite short’ (p. 84), because of the lack of erosion or other disturbance. Again, this points – at least superficially – towards the biblical flood.

Chapter 6 takes us to the topic of radiometric dating. Here we are introduced to the findings of the RATE project (‘Radioisotopes and the Age of The Earth’). It seems clear – even to the young-age creationists in the RATE team – that ‘there has been a lot of radioactive decay’ (p. 96), because of the radiometric dating methods themselves, and also because of the circumstantial evidence from radiohalos and fission tracks. This is an inconvenient truth, and it is highly significant that these researchers find themselves unable to explain it away. Millions of years’ worth of decay has indeed taken place, it seems, and this ‘presents a significant challenge to the idea that the Earth is only thousands of years old’ (p. 97).

The scientific hypothesis provided by the RATE team is that ‘radioactive decay rates were “accelerated” at some time in the Earth’s past’ (p. 99). This (it is suggested) could explain the patterns of discordance between different radiometric dating methods, as well as the continued presence of helium in zircon crystals. But there are significant problems. To express it crudely, the suggestion that God tweaked the radiometric decay rates during the global flood seems quite arbitrary (what purpose would it serve?), and requires further magic tricks in order to prevent the heat from evaporating the oceans, and the radiation from killing the inhabitants of Noah’s ark! (I touched on this in a previous post.)

Chapter 7 explores some evidence for a young age for the solar system and the Earth. This is worth considering, but it is more of a challenge to long-age models than an attempt to build an alternative. Suffice it to say that there are significant problems with conventional long-age models.

Part III (chapters 8-12) deals with Life – Past and present, and we are introduced to some interesting creationist models about biology (drawing particularly on the work of Todd Wood and Kurt Wise).

The idea that living things are descended from a small number of ‘created kinds’ (‘baramins’) resolves various problems with the evolutionary tree of life. For example, there are many similarities between species that cannot be accounted for by common ancestry. ‘In evolutionary thinking, these tree-contradicting similarities cannot have been inherited from a common ancestor and so must have arisen independently in different lineages’ (p. 148).

But there are challenges. First, these models suggest ‘that the baramins diversified to produce many new varieties and species after the Flood’, and that this took place very rapidly (p. 140). One suggestion is that mobile genetic elements might have ‘the potential to produce substantial change in a very short amount of time’ (p. 141). Second, there is the question of predation. ‘Carnivory does not appear to have been part of the natural order at the beginning’ (p. 158). So how do we explain those ‘structures that seem to be beautifully designed, but are used to harm or kill’ (p. 161)? It is suggested that ‘some organisms were designed with the genetic information for structures and behaviour that were unexpressed until sin came into the world’ (p. 162).

Part IV (chapter 13-16) takes us to The Flood and its aftermath. Here we are introduced to three promising areas of creationist research.

First, chapter 13 introduces us to catastrophic plate tectonics. Using computer simulations, geophysicist John Baumgardner has shown that ‘virtually all the original ocean floor’ could have been ‘rapidly “recycled” into the Earth’s mantle during the Flood’, leading to a rapid ‘break-up of the pre-Flood land mass’ (p. 188). This could explain the presence of ‘“cool” slabs of material – apparently remnants of the former ocean crust’ revealed by seismic studies (p. 189). A related model for rapid reversals of the Earth’s magnetic field could also help to explain the patchy nature of the magnetic stripes in the ocean floor (p. 191, 193).

Second, chapter 14 introduces us to ecological zonation theory. According to this theory, the pre-Flood world was arranged into clearly-demarcated ecological ‘zones’, each with its own characteristic species. These ‘zones’ would have been buried in sequence in the Flood, leading to the patterns we observe in the fossil record. So, working from the ocean inwards, there would have been a stromatolite reef, then a shallow sea (trilobites, for example), then a massive floating forest (responsible for the Palaeozoic coal seams), then some coastal dunes, and then the main continental land mass, with dinosaurs living nearest to the ocean.

Third, chapter 15 considers the idea that the global flood might have caused a (single) ice age, drawing on the work of Michael Oard. The post-Flood combination of warm oceans and cooler summers (caused by volcanic dust) would have led to rapid glaciation. Alternative explanations are provided for supposedly annual layers of ice, and the presence of non-glacial deposits between layers of glacial sediments (conventionally understood to be evidence of warm ‘interglacial’ periods). Several lines of evidence seem to point to there having been a single ice age, such as the fact that ‘Nearly all the extinctions of large mammals occurred after the “last” ice age’ (p. 225).

All-in-all, and with copious references, Paul Garner’s book is an excellent introduction to recent thinking in the science of creationism.

But is it convincing? Do the creationist models seem to have any plausibility?

It’s a mixed bag. There are definitely some promising ideas, which merit further investigation. Some of the models are very interesting indeed (to someone who lacks relevant expertise, admittedly). But when it comes to cosmology and to radiometric decay, the problems caused by assuming a young age seem vastly to outweigh the benefits.

It is tempting to be creative, and to suggest that the universe is old but that life on Earth is recent. But that doesn’t resolve the problem of radiometric decay, as many of the geological layers showing evidence of decay would have been laid down during or after the Flood.

Now, these problems with young-age models don’t rule out the possibility that someone will come up with some bright ideas in the years to come. And I don’t want to rule that out. I don’t think we should be afraid to say, ‘I don’t know’. But, in my personal quest for truth, I think I need to jump over to the ‘Religion Domain’ in Leonard Brand’s diagram, at least for a short excursion, and carefully examine some of the (many) attempts to reconcile long-age theories with the Christian faith.