A revised (2014) edition of this book had been released before I started reading the first (2004) edition. But I bought my copy years ago, and I’m sufficiently northern for it to be unthinkable to buy a second copy of the same book. Besides, the new edition added ‘about 150 new pages’ to the already lengthy first edition (424 pages in small print), and that’s quite long enough already.

A revised (2014) edition of this book had been released before I started reading the first (2004) edition. But I bought my copy years ago, and I’m sufficiently northern for it to be unthinkable to buy a second copy of the same book. Besides, the new edition added ‘about 150 new pages’ to the already lengthy first edition (424 pages in small print), and that’s quite long enough already.

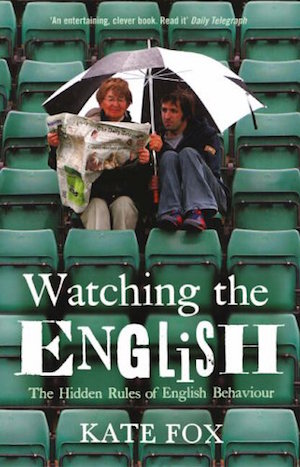

Kate Fox considers herself a ‘maverick-outsider’ to academic anthropology, but seems to be fairly well regarded nonetheless. As co-director of the Social Institutes Research Centre (SIRC) in Oxford, she is ‘a social anthropologist and bestselling author of popular social science books’. ‘Watching the English’ has sold more than half a million copies, and it’s a fascinating and enjoyable read. It’s definitely opened my eyes to many aspects of what it means to be English.

The ‘core’ of Englishness, says Fox, is our acute social dis-ease (p. 401).

We suffer from a congenital sociability-disorder, a set of deeply ingrained inhibitions that make it difficult for us to express emotion and engage in the kind of casual, friendly social interaction that seems to come naturally to most other nations (p. 263).

As such, we are most comfortable in our own private worlds. So ‘home is what the English have instead of social skills’ (p. 134, 172), and interactions in public, such as on public transport, are governed by the ‘denial rule’, which ‘requires us to avoid talking to strangers, or even making eye contact with them, or indeed acknowledging their presence in any way unless absolutely necessary’ (p. 139).

This ‘social dis-ease’ is brought into tragically sharp relief by the realisation that the average Englishman

will have no difficulty at all, however, in engaging in lively, amicable conversation with a dog. Even a strange dog, to whom he has not been introduced. Bypassing the usual stilted embarrassments, his greeting will be effusive: ‘Hello there!’ he will exclaim, ‘What’s your name? And where have you come from, then? D’you want some of my sandwich, mate? Mmm, yes, it’s not bad, is it? Here, come up and share my seat! Plenty of room!’ (p. 235)

What possible hope do we have, particularly those of us who do not have a dog? The solution is our ‘ingenious use of props and facilitators’ (p. 239).

The English are capable of engaging socially with each other, but we need clear and precise guidelines on what to do, what to say, and exactly when and how to do and say it. Games [as well as social pursuits, pastimes, etc.] ritualize our social interactions, giving them a reassuring structure and sense of order. By focusing on the detail of the game’s rules and rituals, we can pretend that the game itself is really the point, and the social contact a mere incidental side-effect (p. 241).

This one of many examples of English self-delusion.

One of our main ‘reflexes’ to our sense of social dis-ease is our famous English humour.

Humour is our most effective built-in antidote to our social dis-ease. … Virtually all English conversations and social interactions involve at least some degree of banter, teasing, irony, wit, mockery, wordplay, satire, understatement, humorous self-deprecation, sarcasm, pomposity-pricking or just silliness (p. 402).

This is closely linked to our knee-jerk reaction to any hint of earnestness.

The taboo on earnestness is deeply embedded in the English psyche. … Key phrases include: ‘Oh, come off it!’ (Our national catchphrase, along with ‘Typical!’) (p. 402-3)

This is particularly apparent when it comes to our ‘woolly beliefs and noncommittal attitudes’ to religion.

We are not only indifferent but, worse (from the Church’s point of view), we are politely indifferent, tolerantly indifferent, benignly indifferent. … Other people are very welcome to worship Him if they choose – it’s a free country – but this is a private matter, and they should keep it to themselves and not bore or embarrass the rest of us by making an unnecessary fuss about it. (There is nothing the English hate more than a fuss.) (p. 355-6)

(I wonder whether there is a deep-seated aversion to genuine Christianity at the heart of our English values…?)

Many more topics are covered: the weather (of course), rules of conversation, work, play, dress, food, sex, and rites of passage, all tinged with our acute class consciousness. Well worth reading.